The next day, she was having to grovel from the police station. Such was the case of one young woman in the Jalal-Abad region, who took to social media on April 11 to call fellow Kyrgyz citizens a bunch of “stinkers” and vowed to leave the country when the crisis passed.

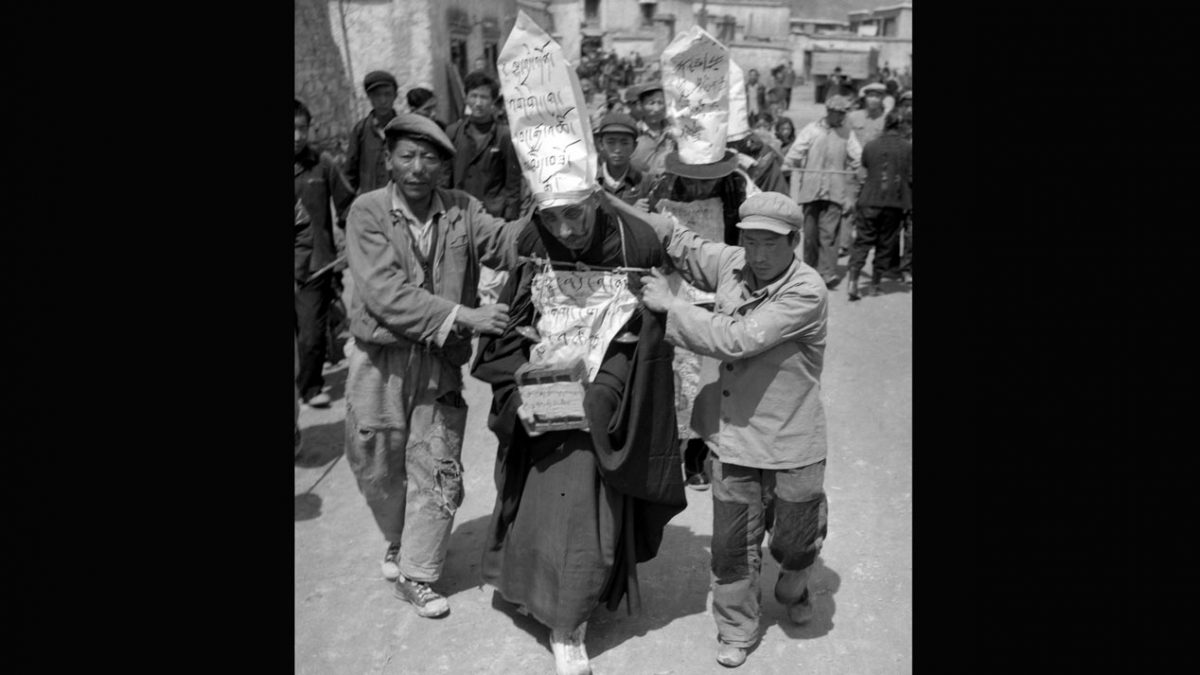

Lockdown and the isolation that it brought with it has strained many people’s patience and enfeebled their judgement. “I apologize for spreading this inaccurate information,” the young man says, as he puts a mask over his mouth, a gesture that was widely interpreted as a nod to the fact that he was being gagged by his superiors. Soon after, a video appeared featuring the same doctor. In April, a doctor in the Ysyk-Ata district, east of the capital, Bishkek, posted a message online to say that medical workers were being given poor-quality PPE. By the end of the month, Talas region had announced its first cases. A pair of women in the Talas region were caught by police spreading a claim that people had been diagnosed with the virus and were then required to recant to camera, albeit with their faces blurred. In early March, before there had been any confirmed cases, rumors flew around liberally on messaging apps. It is not always evident that the apology is justified, however. The coronavirus outbreak has been at the root of many video apologies in Kyrgyzstan too. “I was drunk, so I began to abuse the animal.” “The dog got out and tramped on the seedlings in the greenhouse that had been planted by my parents and tore up the plastic sheets,” Zhumatayev said. The original incident was filmed by Zhumatayev’s acquaintance and was then shared online. His voice breaking, Talgat Mukashev said that what his son had done was an accident.Įarlier this month, a man from Atyrau, Margulan Zhumatayev, delivered a video apology for trying and failing (he claims) to strangle a dog with by clamping its neck in a fridge door. In May, the father of an off-duty police officer who fatally ran over two fellow policemen at a checkpoint into Almaty begged Kazakh citizens for forgiveness for his son. Grimmer episodes occurred in the months that followed. A humble apology followed shortly after: “I ask you to forgive me ladies and gentlemen." The YouTube channel, which collates Interior Ministry-produced videos, is a veritable treasure trove of such forced appeals. One Almaty resident, identified by police only by the initial D., thought to make light of the situation by claiming that he had become infected and that he intended to commit suicide by shooting himself. Things got more serious in March, as Kazakhstan started to battle its coronavirus outbreak. In one typical video from this series, singer Aikyn Tolepbergen said he was deeply sorry if “somebody had really trusted what I said and went and invested their precious savings.”Ī post shared by Aikyn Tolepbergen on at 4:25am PST In February, a group of celebrities, including singers, actors, and social media influencers, filmed appeals to the public apologizing for promoting the services of what turned out to be a pyramid scheme. But that is not always the case.īarely a month seems to pass in Kazakhstan without somebody groveling for forgiveness on video. Often, there is a pretense of the repentance being voluntary. The modern struggle session requires the offender to deliver an apology or recantation into a camera for footage that is then uploaded to social media or video-sharing platforms. Mao Zedong’s China used the struggle session to drill ideological certainties into its population.Ĭlass enemies would be forced to kneel before crowds, declaiming their guilt for some perceived transgression while an assembled crowd pelted them with abuse.Ī practice with similar undertones – albeit with a high-tech twist – has become commonplace in parts of the former Soviet Union, and especially so in Central Asia. He admitted to involvement in bribe-taking and embezzlement.

Former Turkmen Interior Minister Isgender Mulikov, who had been fired some weeks before, appeared on national television news in handcuffs, black prison garb and with his head shaven.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)